How can Big Data help museums reinvent themselves? How can data collection techniques be used to understand visitors better? How can data be used to build visitor loyalty?

In this article, we propose a series of reflections on current and future museographic devices and on “data” initiatives that can be put in place to improve the customer experience and increase visitor loyalty.

Summary

- Introduction

- Museums in the Age of Big Data

- For better exploitation of digital traces

- Conclusion

- Sources

Introduction

At a time when the COVID-19 crisis is severely impacting all the players in the cultural world, it has never been more important for museums to know their “customers” and build their loyalty. However, one problem for the major museums is the large proportion of neo-visitors: 60% of visitors to the Louvre, for example, had never been there before. Understanding the behaviour of these first-time visitors is essential, to serve them better and make them come back. On the other hand, each museum can count on a portion of very loyal visitors whose expectations and behaviour are different from those of first-time visitors.

Proposing specific approaches for each type of visitor, offering them unique customer experiences, are vectors of satisfaction and loyalty.

However, it must be noted that significant museum institutions are not the most innovative in terms of marketing. Tremendous opportunities are therefore to be seized, particularly by making better use of the digital traces left by visitors. The purpose of this article is to study what is being done in terms of (Big) data in art museums and to propose ideas for better use of data.

60% of visitors to the Louvre are first-time visitors.

Museums in the Age of Big Data

Many museums have opened up to data by digitising their collections and making them available to researchers. The images are accompanied by metadata that allow multiple applications, including the training of image recognition algorithms. The National Gallery in Washington, D.C., for example, organised a datathon at the end of 2019 to make use of the data already available. The 6 teams of data scientists worked mainly on the exhibits themselves.

Open data initiatives in museums

- The Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam) offers on its data page photographs of its collections, metadata for each object, a thesaurus and a catalogue of the collections.

- The Metropolitan Museum (New-York) proposes images of its works as well as a catalogue of the collections.

- The National Gallery in Washington offers a digital library of the exhibits in its collections.

- The Italian Ministry of Culture (MBACT) proposes an open data initiative on this page.

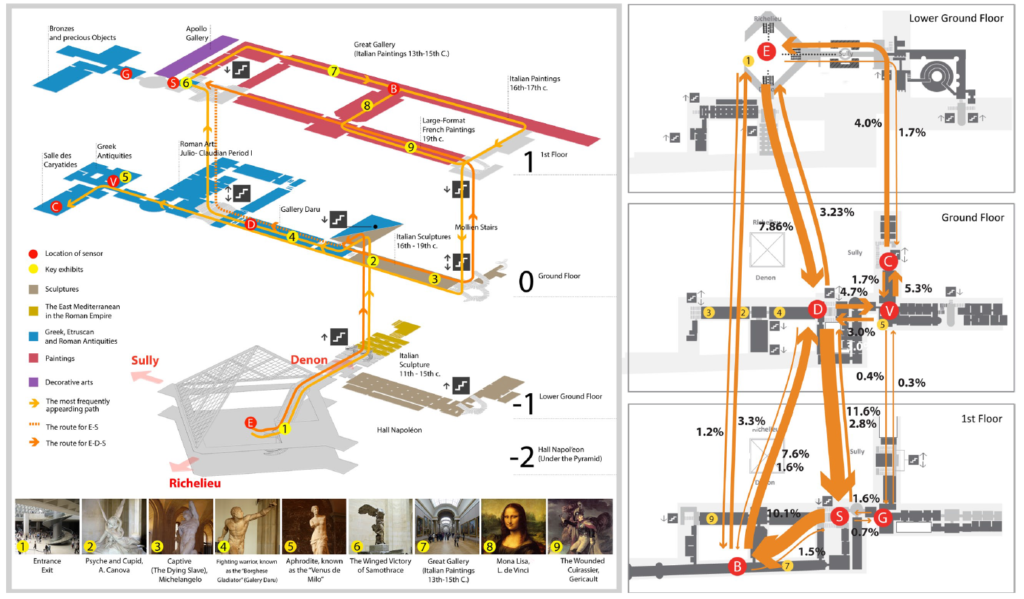

However, apart from this type of initiative, it must be acknowledged that “data” projects are relatively rare. This observation is a little like that made by Anne Krebs in an article in “Grande Galerie”, the newspaper of the Louvre Museum. In this article, she gives an overview of the initiatives taken by the Louvre in the framework of 3 research programmes on Big Data. Among the projects discussed in detail, I was particularly interested in the study of the flow of visitors inside the museum. Carried out by a team of 7 American, Swiss and Spanish researchers, the study made it possible to quantify and visualise the flow of visitors inside the Louvre. To carry out this study, Bluetooth detectors were used, which allow the tracking of mobile phones with the Bluetooth function activated.

This technique, used for the first time in a large museum such as the Louvre, provides interesting behavioural information: how do visitors move around (in general)? What routes do they take according to the time they spend within the museum? In what order do they move through the rooms? The information resulting from such a study represents an extraordinary potential for analysing the different visitor segments, optimising visits, simplifying travel, and simply understanding how visitors consume the works of art.

This project at the Louvre parallels another initiative. In the Netherlands, the tablets lent to visitors to the Van Gogh Museum to guide them are tracked using beacons. This technique also makes it possible to retrace the paths of visitors inside the museum. The beacons also have the advantage of being able to send notifications to the smartphones and tablets connected to them; an excellent way to interact with visitors and improve the customer experience.

But such initiatives are still rare. One thing is exact: museums deploy a wealth of energy to make information available to the public. However, they forget to use the data to understand their audiences and serve them better.

Museums expend a wealth of energy in making information available to the public. However, they forget to use data to understand their audiences and serve them better.

Digital tracks that could be better exploited

The millions of visitors who flock (or used to flock before COVID) to major museums are an inexhaustible source of “megadata” (Big Data). Multiple initiatives could be put in place to answer questions such as:

- What are the visitors’ itineraries inside the museum grounds?

- Which works “retain” visitors the longest?

- How do visitors use the media?

- How do the itineraries of first-time visitors differ from those of regular visitors?

In a nutshell, how do visitors “consume” the museum?

Digital devices are abundant that would enable the collection and exploitation of “cultural” data. Designed as visitor supports (touch screens, mobile applications), these devices could also be used to understand the behaviour of visitors (cf. the Van Gogh museum project with the beacons). In the table below, I let myself imagine new uses for the most commonly encountered devices: touch screens, audio guides, mobile applications. Some exploitations are undoubtedly directly possible. Others require hardware adaptations to allow data collection.

| Device | Actual use | Possibility of data analysis |

| Touch screens | Search for information / deepening research |

How do visitors search on the screen? How much time do they spend looking at the available information? Are some screens used more than others? |

| Mobile applications | Guiding / finding information |

Use of Bluetooth sensors or beacons to monitor visitor flows inside the museum Reconstruction of the visitor’s route based on the information used. Identification of the most requested exhibits in the app |

| Audio guide | Provide audible information as the visit progresses |

By adding a Bluetooth chip for a few pence to be able to follow the audio guide via beacons (currently the tracking of the audio guide is best done via RFID). Reconstruction of the visitor’s route based on the audio information consumed Analysis of audio guide reading information (how did the visitor use the audio guide? What information was consumed? Which works were studied in greater depth? |

In addition to the edutainment systems already in place, more confidential initiatives also exist. Elena Stylianou (2012), for example, mentions the experience at Tate Britain during the exhibition “Constable: The Great Landscapes”. An interactive device was implemented, which allowed the visitor to discover the x-ray images of an exhibit using motion recognition

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis poses an existential threat to cultural institutions.

Understanding visitor behaviour is essential to be able to offer unique customer experiences that build visitor loyalty.

Current digital devices, and others yet to be developed, are sources of data on visitor behaviour. Exploiting them would allow a better understanding of the museum experience. In doing so, visitors could be targeted, and specific customer experiences put in place to increase visitor satisfaction. In turn, a loyalty strategy could be put in place to convert first-time visitors into loyal customers of the museum.

Sources

Krebs, A. (2019) Musée et “mégadonnées” : partenariats de recherche au musée du Louvre. Grande Galerie, Hors-Série, pp 10-17.

MeeCham, P., & Stylianou, E. (2012). Interactive technologies in the art museum. Designs for Learning, 5(1-2), 94-129.

Posted in big data, Marketing.